Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol

A blog dedicated to the making of the first animated Christmas special, Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol.

Thursday, December 23, 2010

Merry Christmas!

Monday, December 20, 2010

Sponsors for Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol

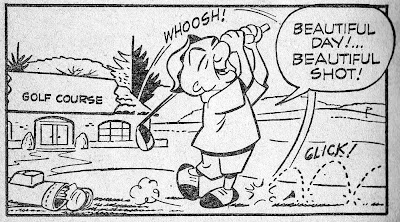

As mentioned in my book, Lee Orgel, producer of Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol, engaged in a rather lengthy search for a sponsor in order to get the special on the air. During that process, one sponsor that expressed interest was Carling Ale, who had previously used Mr. Magoo in 1958 for a year long advertising campaign for one of their labels, Stag Beer. No memos explaining their decision to decline sponsorship have been found but one possibility is that there had been a sea change in how Magoo was perceived in the few short years between 1958 and 1962.

As discussed in a previous post, Chris Hayward, staff writer at Jay Ward, in a letter to Abe Levitow in 1963, analyzed that change:

When the character first erupted on the screens, he was dug by kids but I think mostly by adults, appealing to that select group of connoisseurs who rapture joyously over the (John) Hubley and (Ernie) Pintoff offerings...The five minute cartoon TV series wiped out the avant garde fans, capitalizing instead on the tousled-haired set from five to fifteen.

It’s possible that Carling, NBC or even Lee Orgel realized that having a beer company sponsor a family special might not have been in anyone’s best interests. To give you an idea of what Christmas with a beer drinking Magoo looked like, here’s an ad for Stag Beer from 1958:

As we all know, Timex was the eventual sponsor of the show. Here are some rare frames from the end bumpers of the special:

As discussed in a previous post, Chris Hayward, staff writer at Jay Ward, in a letter to Abe Levitow in 1963, analyzed that change:

When the character first erupted on the screens, he was dug by kids but I think mostly by adults, appealing to that select group of connoisseurs who rapture joyously over the (John) Hubley and (Ernie) Pintoff offerings...The five minute cartoon TV series wiped out the avant garde fans, capitalizing instead on the tousled-haired set from five to fifteen.

It’s possible that Carling, NBC or even Lee Orgel realized that having a beer company sponsor a family special might not have been in anyone’s best interests. To give you an idea of what Christmas with a beer drinking Magoo looked like, here’s an ad for Stag Beer from 1958:

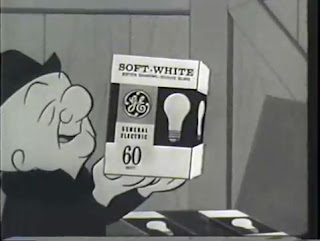

Another question, which I touch on in the second edition of the book, was why didn’t General Electric sponsor Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol? They had been using Magoo since 1959 to sell lightbulbs:

GE was the obvious, and most natural choice, to sponsor the special. I found nothing in my research on why they didn’t pick up the tab for the show although it’s quite possible they had already committed their ad budget for the year. In any event, it appears they realized their error after the success of the special and later tried to get back on board, offering to pay three-quarters of the sponsorship costs for only half of the show. Timex, the show’s final sponsor, wouldn’t budge. A couple of years later, GE did end up wholly sponsoring Rankin Bass’s Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer to promote their small appliances.

As we all know, Timex was the eventual sponsor of the show. Here are some rare frames from the end bumpers of the special:

Monday, December 13, 2010

The Unknown Christmas Carol

In several previous posts, I've discussed material that did not make it into the final production. Items of interest continue to surface and I thought I would list them here. It is by no means complete as I expect there is even more material to be found. There is some repetition from both the book and this blog but I thought I would create as complete a list as possible. (Above, the cat who never was, just outside the back entrance of the restaurant.)

Title sequence-The original titles started with a long shot of buildings with flashing neon signs. Two of those signs flashed Timex, the show's original sponsor. The camera then panned over to the existing title card of Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol. Title length was the same; the current version cycles the show's title card to cover the missing Timex credit.

Title sequence-The original titles started with a long shot of buildings with flashing neon signs. Two of those signs flashed Timex, the show's original sponsor. The camera then panned over to the existing title card of Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol. Title length was the same; the current version cycles the show's title card to cover the missing Timex credit.

Prologue-As I mentioned in the book, the original version of the song, "Back on Broadway", included an entire middle section of in which the waiters at the deli chime in at key moments in the song. Styne and Merrill sang those lyrics in their demo recording and the extant sheet music also contains those lyrics. A recently discovered photocopy of a layout shows that at one point, we did go inside the restaurant with Magoo.

Inside the theater-Another recent discovery shows a much more intimate version of the well-used audience shot. It went through at least one more iteration before the final version we know from the film.

Scrooge's office-After Scrooge puts on his coat and scarf and exits, there was a scene of him at his front door in which he turns off the light and exits, slamming the door. The folder with the cels of the lighting masks still exists, sans Magoo.

Inside the theater-Another recent discovery shows a much more intimate version of the well-used audience shot. It went through at least one more iteration before the final version we know from the film.

Scrooge's office-After Scrooge puts on his coat and scarf and exits, there was a scene of him at his front door in which he turns off the light and exits, slamming the door. The folder with the cels of the lighting masks still exists, sans Magoo.

Scrooge's walk home-Here you can see an extremely rare deleted composite layout by Bob Singer from Scrooge's walk home in the snowstorm. This came immediately after he exited what is now the last scene in that sequence. Scrooge would have walked through the scene on the sidewalk in front of the hot chestnut vendor. The next scene which starts the following sequence shows him approaching his house.

Scrooge's house-The original Marty Murphy storyboards for this sequence show the inside of Scrooge's house in a scene almost identical to the deleted background on p. 67 in the book, where the door slams behind Scrooge, foreshadowing Marley's arrival. Based on a surviving production draft, that material was never even laid out. However, the background in the book was meant for a scene in which a "pulsating shape turns into Marley's ghost". Below, Shirley Silvey's layout showing Marley's ghost after he is no longer a "pulsating shape". It's believed that the shape moved from the left of the railing to end in this final position.

Visit by Marley's Ghost-Apparently, the scene in which Scrooge cringes as Marley's ghost flies over him before exiting did not have the ghost's shadow passing over Scrooge in the 1962 version. The folder for that scene has a retake date of 8/31/1963 in which the shadow pass was added. Curious that almost a year later, they were making changes to the picture.

The Ghost of Christmas Past-Apparently, Lee Mishkin had a more aggressive approach to this ghost's visit.

Scrooge's visit to his school-The previous post on Bonus Features for the upcoming DVD had a picture of a character, Mrs. Halsey, that was designed, inked and painted but cut from the final film.

Fezziwig's/Winter Was Warm-As mentioned in the post Christmas Belles, this entire sequence was re-animated after being laid out, animated, inked, painted and shot with a different model of Belle. Also discussed in the book, "Winter Was Warm" was over twice as long, with an instrumental interlude and a second verse.

The Ghost of Christmas Past's exit-Shortly after the 32 minute mark, in Belle's parlor, the Ghost tells Scrooge, "One shadow more." There is a ripple dissolve to limbo, with Scrooge pleading on his knees, when the Ghost laughs and rises up out of the scene. The "one shadow more" sequence would have been where Scrooge sees Belle's future life with her husband and children. It's the only deleted sequence to actually have been assigned a sequence number and it's odd that the scenes would have been laid out with a continuity break, even if the sequence had been deleted in the storyboarding stage. What seems likely is that the missing sequence had been at least laid out, if not animated, but no drawings or cels have yet been discovered for this sequence.

End bumper-The end of the original show had a short Timex bumper, boarded and laid out by Bob Singer, wishing the viewers "a very Merry Christmas" and reminding them that "More people give Timex than any other watch in the world." (Below, a composite board made from two pages of Singer's boards.)

End credits-Another retake from the 1962 version; during September of 1963, the end credits were reshot, changing two cards. It appears that Lee Orgel had once again been given Associate Producer credit, the same credit he received on Gay Purr-ee. In both cases, Orgel functioned as Producer but was denied the screen credit (i). I have found no paperwork regarding why this credit change was implemented but Orgel did leave UPA in 1963, apparently unhappy that promised profit participation in Christmas Carol and Gay Purr-ee was not forthcoming.

The other credit that was changed was the second to last card and although there is nothing to indicate the precise change, a reasonable guess is the addition of Stephen Bosustow's credit, Mr. Magoo created under the supervision of Stephen Bosustow. As part of Saperstein's 1960 agreement with Bosustow to buy the company, UPA was contractually bound to include this particular credit on all Mr. Magoo productions.

(i) Originally, Peter DeMet, Henry Saperstein's business partner, was to receive Producer credit on Gay Purr-ee but that credit was deleted, perhaps due to his exit from UPA's affairs. No one receives Producer credit in the final film; Orgel had to settle for Associate Producer.

Thursday, December 9, 2010

UPA's lost year

Despite the overwhelming positive response to Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol, the studio largely lay fallow through 1963. Once again, as was (and still is) common for animation studios, most of the staff had been let go at the end of production and only a few key artists stayed on, in this case, to handle the demands of the General Electric TV commercials featuring Magoo. Mr. Magoo was considered an “in” property at the time and continued to generate income through licensing and merchandising even if he wasn’t actively utilized in production. Saperstein expanded his Magoo empire by developing and selling a Mr. Magoo comic strip to the Los Angeles Times Syndicate around this time. (Above, a panel from the strip, drawn by the versatile Pete Alvarado.)

But considering the success of the special, it's a bit puzzling that, aside from the TV commercials, Magoo made no new broadcast or film appearances during 1963. Without having access to the UPA production records, it's difficult to know exactly what happened during this "lost" year. What seems likely, though, is that UPA had been caught flat footed with the unexpected success of the special. In Hollywood, success demands more of the same so it's not unreasonable to assume that NBC immediately requested a follow up and UPA would have had to scramble to come up with something.

Some of the answer to what happened in 1963 might be in a letter recently discovered in Abe Levitow's files. Although it seems like a natural progression to take the central conceit of Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol, Magoo as an actor in literary classics, and expand it into a series, this letter indicates that the path was anything but a straight line. The letter, dated June 6, 1963, addressed to Abe Levitow, is from Chris Hayward, one of the staff writers at Jay Ward (Hayward is credited as the creator of Dudley Do-Right and future co-developer of The Munsters). It's unusual for competing animation studios to collaborate, but in my book I note the frequent interchange of personnel between UPA and Jay Ward throughout the 1960s. Now, it appears that the relationship between the two studios might have been even closer than first realized.

Hayward begins:

I think we can now generally agree that depositing Magoo in a proper and saleable vehicle provides with us what we can label one hell of an enigma.

When the character first erupted on the screens, he was dug by kids but I think mostly by adults, appealing to that select group of connoisseurs who now rapture joyously over the Hubley and Pintoff offerings.

In his next paragraph, he nails the central problem with the then current incarnation of Magoo:

The five minute cartoon TV series wiped out the avant garde fans, capitalizing instead on the tousled haired set from five to fifteen.

He continues to analyze the situation and then begins his proposal:

Currently in vogue is the dashing James Bond character, hero in sundry novels and recently in motion pictures. Bond is the epitome of the secret secret service agent, thriving on deadly action, good booze, and an unending stream of delectable broads.

...Anyway, it might be fun making Magoo into a blase, man-of-the-world crime-solver, maintaining a lush penthouse suite in Manhattan, dining in elegant bistros educating an already glutted epicurean palate, pursued by a coterie of lovely vixens smitten by his ruddy maturity, and dedicating the twilight years of his life bringing scoundrels to justice.

At no point was Hayward suggesting that UPA continue to capitalize on Magoo's nearsightedness. Instead, he saw Magoo as an adult level character again, although he may have been overreaching by pitching Magoo's involvement with the three Bs, booze, broads and bad guys. It was an intriguing notion but once a character has crossed into the juvenile market, it's virtually impossible to bring them back. Most likely UPA realized that as well, as the matter appears to have been dropped. Hanna Barbera later capitalized on the Bond craze, albeit with less panache than Chris Hayward was suggesting, with their feature length film, The Man Called Flintstone. And Hayward did get to explore his takeoff on the James Bond films when he wrote for the spy spoof TV series, Get Smart.

Eventually, the studio did adopt the idea of Magoo starring in literary classics, which became The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo. This correspondence makes one wonder, though, what other proposals were explored during that year to capitalize on the success of Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol?

Labels:

Abe Levitow,

Chris Hayward,

General Electric,

Mr. Magoo

Monday, December 6, 2010

The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo

Many of the readers of this blog grew up not only with Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol but also with the prime time series that it spawned, The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo. For many, it was their first exposure to the classic literature that was the basis for the show. The series, although memorable, unfortunately did not achieve any where near the ratings success of the Christmas special.

However, its production was rather remarkable. From NBC’s greenlight in January to the show’s debut in September, the staff was quickly enlarged, multiple writers were attached to the series and much of the animation was farmed out to freelancers all over Los Angeles. In less than nine months, UPA pumped out 26 half hours of hand drawn animation from a standing stop, which is still almost incomprehensible, even in this era of computer assisted production. Above, is a poor quality photocopy from a trade magazine of the time, showing Hank Saperstein and some of the animation crew on the show. You'll notice that it looks a bit crowded there. There's only one room in any office that's long and narrow like that and that's a hallway, which gives you an idea of the intensity of production. No one who worked at UPA recalls a hallway like that so it's possible this was a crew at a satellite facility. (Below, the original model sheet for the debut episode, William Tell, probably drawn by Bob Dranko.)

However, its production was rather remarkable. From NBC’s greenlight in January to the show’s debut in September, the staff was quickly enlarged, multiple writers were attached to the series and much of the animation was farmed out to freelancers all over Los Angeles. In less than nine months, UPA pumped out 26 half hours of hand drawn animation from a standing stop, which is still almost incomprehensible, even in this era of computer assisted production. Above, is a poor quality photocopy from a trade magazine of the time, showing Hank Saperstein and some of the animation crew on the show. You'll notice that it looks a bit crowded there. There's only one room in any office that's long and narrow like that and that's a hallway, which gives you an idea of the intensity of production. No one who worked at UPA recalls a hallway like that so it's possible this was a crew at a satellite facility. (Below, the original model sheet for the debut episode, William Tell, probably drawn by Bob Dranko.)

Despite that massive increase of manpower, shortcuts were necessary that would allow the crew to meet that deadline. One of those shortcuts was to avoid animating action within the episodes, relying instead on dialogue to move the story along or in the case of the Moby Dick episode, the use of still art to tell what the budget and schedule couldn't afford. The unfortunate side effect was that the show became very talky making the show less interesting for younger viewers; doing the classics in cartoon form probably made it less likely that adults would watch, both of which might explain why it was not renewed. However, it was suitable family viewing and probably its greatest strength was in introducing classic literature to children. (Below, one of the pieces of still art by layout man Don Morgan for the climax of Moby Dick.)

Abe Levitow was the series' supervising director, underneath him were directors such as Christmas Carol sequence director, Gerard Baldwin, former Looney Tunes director, Bob McKimson and former MGM animator Ray Patterson, who were responsible for individual shows and who would work directly with the animators.

The writers had interesting pedigrees as well. Below is a breakdown of the writing crew, all freelancers, with the shows they wrote. I’ve highlighted each name with a link to their IMDB page. If you click through, you’ll see that these writers worked on many of the classic sitcoms and dramas of the era. You’ll also notice Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol scribe, Barbara Chain, in there.

Walter Black-Robin Hood, 1-4, Count of Monte Cristo, Captain Kidd

True Boardman-Don Quixote, Pts 1 & 2, Moby Dick, Cyrano de Bergerac, Sherlock Holmes

Barbara Chain-William Tell, Snow White, Pts 1 & 2, Noah’s Ark, Rip Van Winkle, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Joanna Lee-Three Musketeers, Pts 1 & 2

Sloan Nibley-King Arthur, Frankenstein, Gunga Din, Dick Tracy

As I pointed out in the book, while the episodes are often slow moving, the visuals are worth a second look. Although the studio had to turn out an entire series in a short amount of time, it gave the design staff the opportunity to experiment without management or network interference. The show contains some appealing character designs and well designed layouts complemented by interesting painting styles. (Below, models by Lee Mishkin.)

Unfortunately, the only episode from The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo to be released on DVD is the feature length Robin Hood series which, because it was stitched together from four separate episodes, is missing scenes from its original broadcasts. (Right, background by Bob Inman from Robin Hood.) Lack of demand for Magoo product has made Classic Media gun shy when it comes to releasing the entire series. Perhaps with enough interest, they can be persuaded to go back into the vaults. You can contact them here.

However, its production was rather remarkable. From NBC’s greenlight in January to the show’s debut in September, the staff was quickly enlarged, multiple writers were attached to the series and much of the animation was farmed out to freelancers all over Los Angeles. In less than nine months, UPA pumped out 26 half hours of hand drawn animation from a standing stop, which is still almost incomprehensible, even in this era of computer assisted production. Above, is a poor quality photocopy from a trade magazine of the time, showing Hank Saperstein and some of the animation crew on the show. You'll notice that it looks a bit crowded there. There's only one room in any office that's long and narrow like that and that's a hallway, which gives you an idea of the intensity of production. No one who worked at UPA recalls a hallway like that so it's possible this was a crew at a satellite facility. (Below, the original model sheet for the debut episode, William Tell, probably drawn by Bob Dranko.)

However, its production was rather remarkable. From NBC’s greenlight in January to the show’s debut in September, the staff was quickly enlarged, multiple writers were attached to the series and much of the animation was farmed out to freelancers all over Los Angeles. In less than nine months, UPA pumped out 26 half hours of hand drawn animation from a standing stop, which is still almost incomprehensible, even in this era of computer assisted production. Above, is a poor quality photocopy from a trade magazine of the time, showing Hank Saperstein and some of the animation crew on the show. You'll notice that it looks a bit crowded there. There's only one room in any office that's long and narrow like that and that's a hallway, which gives you an idea of the intensity of production. No one who worked at UPA recalls a hallway like that so it's possible this was a crew at a satellite facility. (Below, the original model sheet for the debut episode, William Tell, probably drawn by Bob Dranko.)Despite that massive increase of manpower, shortcuts were necessary that would allow the crew to meet that deadline. One of those shortcuts was to avoid animating action within the episodes, relying instead on dialogue to move the story along or in the case of the Moby Dick episode, the use of still art to tell what the budget and schedule couldn't afford. The unfortunate side effect was that the show became very talky making the show less interesting for younger viewers; doing the classics in cartoon form probably made it less likely that adults would watch, both of which might explain why it was not renewed. However, it was suitable family viewing and probably its greatest strength was in introducing classic literature to children. (Below, one of the pieces of still art by layout man Don Morgan for the climax of Moby Dick.)

Abe Levitow was the series' supervising director, underneath him were directors such as Christmas Carol sequence director, Gerard Baldwin, former Looney Tunes director, Bob McKimson and former MGM animator Ray Patterson, who were responsible for individual shows and who would work directly with the animators.

The writers had interesting pedigrees as well. Below is a breakdown of the writing crew, all freelancers, with the shows they wrote. I’ve highlighted each name with a link to their IMDB page. If you click through, you’ll see that these writers worked on many of the classic sitcoms and dramas of the era. You’ll also notice Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol scribe, Barbara Chain, in there.

Walter Black-Robin Hood, 1-4, Count of Monte Cristo, Captain Kidd

True Boardman-Don Quixote, Pts 1 & 2, Moby Dick, Cyrano de Bergerac, Sherlock Holmes

Barbara Chain-William Tell, Snow White, Pts 1 & 2, Noah’s Ark, Rip Van Winkle, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Joanna Lee-Three Musketeers, Pts 1 & 2

Sloan Nibley-King Arthur, Frankenstein, Gunga Din, Dick Tracy

As I pointed out in the book, while the episodes are often slow moving, the visuals are worth a second look. Although the studio had to turn out an entire series in a short amount of time, it gave the design staff the opportunity to experiment without management or network interference. The show contains some appealing character designs and well designed layouts complemented by interesting painting styles. (Below, models by Lee Mishkin.)

Unfortunately, the only episode from The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo to be released on DVD is the feature length Robin Hood series which, because it was stitched together from four separate episodes, is missing scenes from its original broadcasts. (Right, background by Bob Inman from Robin Hood.) Lack of demand for Magoo product has made Classic Media gun shy when it comes to releasing the entire series. Perhaps with enough interest, they can be persuaded to go back into the vaults. You can contact them here.

Thursday, December 2, 2010

Abe Levitow, director

During my interviews with some of the artists and production personnel who worked with Abe Levitow, it became apparent that despite being a highly regarded draftsman, he was a man of few words. Annie Guenther, color modelist on Christmas Carol, who lived near him in Northridge when they both worked at UPA, would sometimes drive him to work when his sports car was experiencing trouble. She remembers that during the lengthy drive to Burbank, Abe spent the entire time thoughtfully puffing on his pipe, never uttering so much as a word. Although every single artist and administrator praised him as being a kind and an unusually supportive director, few could tell me much about him as a person. With enough anecdotes and access to his well kept archives, I was able to form a fairly clear picture of the man but I felt that when it came time to consider candidates for profiles on this blog, perhaps the people most qualified to provide insight into the artist who directed Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol were his family. Following is a remembrance by his three adult children.

“REMEMBERING THE MOOSE” by Judy, Roberta and Jon Levitow

They called him “Moose” in the Army, and the name just stuck. During World War Two he worked for the animation branch of the Signal Corps, the Army’s motion picture division, in New York's Astoria Studios making training films with other writers and cartoonists such as Stan Lee (Marvel Comics), Sam Cobean (The New Yorker, The Naked Eye) , and George Baker (Sad Sack) as well as many other Hollywood animators . There are hundreds of caricatures of our dad as a moose with a huge nose and antlers planted on his head, towering over everyone. He sent our mom Valentines and Anniversary cards with himself as a giant, awkward moose and our mom as a dainty damsel. The caricature really fit him since he was tall, gentle, shy and funny. (Above and below, drawings by Chuck Jones.)

They called him “Moose” in the Army, and the name just stuck. During World War Two he worked for the animation branch of the Signal Corps, the Army’s motion picture division, in New York's Astoria Studios making training films with other writers and cartoonists such as Stan Lee (Marvel Comics), Sam Cobean (The New Yorker, The Naked Eye) , and George Baker (Sad Sack) as well as many other Hollywood animators . There are hundreds of caricatures of our dad as a moose with a huge nose and antlers planted on his head, towering over everyone. He sent our mom Valentines and Anniversary cards with himself as a giant, awkward moose and our mom as a dainty damsel. The caricature really fit him since he was tall, gentle, shy and funny. (Above and below, drawings by Chuck Jones.) Often he communicated better through drawings than through conversation. “Moosey” wasn’t prone to blowing his own horn, but worked with a quiet pride. Even many years later, we’re told of the fierce loyalty he instilled in those who worked with him. People tell us how he encouraged creativity in others and always tried to get the best work from them. When he died too soon in 1975, just short of his 53rd birthday, he fell into a quiet obscurity undisturbed by the animation revival of the 1980’s. It’s thanks to animation historians like Darrell Van Citters that our dad Abe Levitow’s loving contribution to the field will at last be remembered.

Conceived in Ostrolenka, Poland, near the Russian border, our Dad was born in Boyle Heights in East LA in 1922. William Levitow, his very pregnant wife Sarah, and their 2- year- old daughter Frances were part of an early wave of Jewish immigrants leaving Eastern Europe due to the upsurge of anti-Semitism amidst constantly changing borders, armies and governments. “Willie” was originally a Talmudic scholar in Vilna, Lithuania, but left to avoid conscription in the various Russian armies to become an artist in a new media…photography. He loved to tell us grandchildren that back in the Old Country everyone thought he was some kind of magician because he could superimpose an image of a man and make him look like he was sitting on a horse. When he came to Los Angeles, he worked as a photo-retoucher for 20th Century Fox and made all the stars’ defects disappear. Willie joined the IATSE #683 film laboratory technicians strike in 1945, found himself on the blacklist and never worked again for the studios. As far as we could tell, from then until after “Willie” grew too weak to lift boxes at his brother-in-law’s grocery store, our grandparents lived on the rents in the little quadraplex they owned on Fountain Avenue in Hollywood.

It was our grandmother who really nurtured our father’s drawing talent. Sarah was passionately involved in Los Angeles’ early Yiddish culture scene and she counted many artists among her friends. She encouraged young Abe to pursue his evident talent and sent him to Saturday art classes. As a teenager, Dad sent away for and completed mail-order cartooning classes from the W.L. Evans School of Cartooning. After he graduated from Roosevelt High School, Dad won a scholarship to Chouinard School of Art (which eventually evolved into the California Institute of the Arts). Our grandmother encouraged Abe to walk his drawings virtually across the street to the Leon Schlesinger studio on the Warner Bros. lot. It was long spoken of as one of the family miracle stories that, on the spot, Chuck Jones hired him as an in-betweener. Dad never left the animation business after that. In gratitude, Chuck got one of our grandmother’s delicious European-style cheesecakes every Christmas time. We never knew if it was the cheesecakes or not, but they marked a long alliance between Chuck and our father. They worked together at Warner Brothers, MGM and ABC. Another benefit of animation was that Abe met our mother Charlotte, an award winning artist in her own right, who was an ink & painter at Warner Brothers. They married in 1949. (Below, a 1954 shot of Abe at Warner Bros., just after he began receiving screen credit. Seated at the desk is animator Dick Thompson.)

It was our grandmother who really nurtured our father’s drawing talent. Sarah was passionately involved in Los Angeles’ early Yiddish culture scene and she counted many artists among her friends. She encouraged young Abe to pursue his evident talent and sent him to Saturday art classes. As a teenager, Dad sent away for and completed mail-order cartooning classes from the W.L. Evans School of Cartooning. After he graduated from Roosevelt High School, Dad won a scholarship to Chouinard School of Art (which eventually evolved into the California Institute of the Arts). Our grandmother encouraged Abe to walk his drawings virtually across the street to the Leon Schlesinger studio on the Warner Bros. lot. It was long spoken of as one of the family miracle stories that, on the spot, Chuck Jones hired him as an in-betweener. Dad never left the animation business after that. In gratitude, Chuck got one of our grandmother’s delicious European-style cheesecakes every Christmas time. We never knew if it was the cheesecakes or not, but they marked a long alliance between Chuck and our father. They worked together at Warner Brothers, MGM and ABC. Another benefit of animation was that Abe met our mother Charlotte, an award winning artist in her own right, who was an ink & painter at Warner Brothers. They married in 1949. (Below, a 1954 shot of Abe at Warner Bros., just after he began receiving screen credit. Seated at the desk is animator Dick Thompson.)Dad was always a little self-conscious about not having gone to college. But he never stopped educating himself - reading, seeing plays or movies. Throughout his career he continued life-drawing classes. Our Sunday afternoon family outings were most likely to be a trip to the latest exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Fine art books filled our family bookshelves, and Dad had a particular love for the work of powerful draftsmen like Mexico’s Francisco Zuñiga and David Siqueiros.

Abe Levitow’s career went on to span over 35 years. He progressed from in-betweener, to animator, to animation director. (Above, some of Abe's late '50s doodles.) Besides his work with Chuck Jones, he spent a number of years at UPA and worked with Richard Williams in London and LA (below, an original cel setup from Richard Williams' version of A Christmas Carol). We couldn’t be prouder of him and his accomplishments. He’s listed as an animator on eight of Jerry Beck’s “The 100 Greatest Looney Tune Cartoons”, although he had begun animating years before he received screen credit. He directed late-UPA favorites Gay Purr-ee and Mister Magoo's Christmas Carol. Many kind testimonials fill our guest book at www.abelevitow.com, a website we created to help bring his wonderful talent back to aficionados of animation history.

In 1971, after decades of supporting so many other studios' efforts, he finally struck out on his own, forming Levitow/Hanson Films. But just two years after realizing that dream, he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a bone cancer that painfully reduced his former Moose-like stature. Dad loved animation and never stopped working until he just couldn’t manage the effort, finally succumbing in 1975. (Below, Levitow and crew in front of their office in the Walter Lantz building in Hollywood. Christmas Carol alums Tony Rivera and Steve Clark are on the left.)

We remember our father as a homebody, not much of a traveler - someone who loved nothing more than spending the evening and weekends doing ink drawings with his kids, working on clay sculptures, and exploring his oil paints. He even painted sets for the local Northridge Theatre Guild. He charmed our mom’s huge extended family and especially all the kids and cousins. He enjoyed summers in San Diego, where we shared an extended-family house at the beach and where he delighted in beach softball and water sports. For a towering man of 6’4”, he was surprisingly gentle. Sometimes he seemed lost in his own thoughts, but if he was in the mood, he could keep the kids and grown-ups laughing hysterically at funny stories or his funny voices. At family gatherings, “Moose” was always the large man with all the little kids crawling all over him, shooting hoops with the older kids in the backyard, or drawing a funny picture of Bugs Bunny or the family dog—whatever struck someone’s fancy.

We remember our father as a homebody, not much of a traveler - someone who loved nothing more than spending the evening and weekends doing ink drawings with his kids, working on clay sculptures, and exploring his oil paints. He even painted sets for the local Northridge Theatre Guild. He charmed our mom’s huge extended family and especially all the kids and cousins. He enjoyed summers in San Diego, where we shared an extended-family house at the beach and where he delighted in beach softball and water sports. For a towering man of 6’4”, he was surprisingly gentle. Sometimes he seemed lost in his own thoughts, but if he was in the mood, he could keep the kids and grown-ups laughing hysterically at funny stories or his funny voices. At family gatherings, “Moose” was always the large man with all the little kids crawling all over him, shooting hoops with the older kids in the backyard, or drawing a funny picture of Bugs Bunny or the family dog—whatever struck someone’s fancy. "Remembering the Moose" copyright 2010 by Judy Levitow, Roberta Levitow and Jon Levitow

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

Happy Thanksgiving!

The above drawing was done by Abe Levitow as pitch art for a never produced episode of The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo. May you and your family have a safe and Happy Thanksgiving!

And if you're in Los Angeles this weekend, don't forget about the screening of Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol with Marie Matthews, Jane Kean and Bob Singer at the Egyptian Theater. If you'd like a copy of the book signed by the panel participants, you can pre-order a copy here.

Thursday, November 18, 2010

Christmas Belles

One of the biggest pleasures in writing the book was finding out how many people loved the special and were excited to read about its genesis. One of those was a fellow animator, who visited me at my office to buy a copy of the book last year and whose interest in animation dated back to his teen years in the early 1960s. He used to haunt the dumpsters in back of the various animation studios around Los Angeles and his rescue efforts paid off in some rather unique and interesting finds.

At UPA, for example, he discovered Abe Levitow's original model sheet drawings for the 1960s Mr. Magoo model in the trash,

as well as some of the most unusual items from the special to come to my attention. As he went through his stack, he showed me some cels from the show-not just the standard production cels but cels which had a very different version of Belle on them. This Belle was the one designed by Tony Rivera,

and not the one we know from the special, as designed by Lee Mishkin.

Unlike the cels of the Tony Rivera’s three ghosts depicted in the book (p. 84), these were not suggested model cels of Belle but the same model from three different scenes, sequentially numbered, indicating they were random cels from those scenes. These were production cels!

To say the least, it was a rather stunning find. Later, another collector showed me a character layout with the same model of Belle, yet more evidence of a mid-production change. Recently, I had the chance to examine the original scene folders for this sequence and found notes on them indicating that the scenes had indeed been re-animated. There's no doubt this sequence was first animated, inked, painted and shot using the Tony Rivera model of Belle.

I mention this in the audio commentary track on the new DVD release but here you have the opportunity to see the difference first hand. Tony's model of Belle, while simple, is still appealing but the animator for these scenes seems to have completely lost the charm inherent in the original design. As the DVD feature "From Pencil to Paint" shows, the animators relied heavily on the character layouts as guides for their animation, consequently the layout artist for this sequence also shares some responsibility. Rivera's clean graphic design has deteriorated into a series of undulating lines defining virtually nothing. A sensitive hand was needed to translate his graphic sensibility into animation; lacking that, a new approach was required.

At UPA, for example, he discovered Abe Levitow's original model sheet drawings for the 1960s Mr. Magoo model in the trash,

as well as some of the most unusual items from the special to come to my attention. As he went through his stack, he showed me some cels from the show-not just the standard production cels but cels which had a very different version of Belle on them. This Belle was the one designed by Tony Rivera,

and not the one we know from the special, as designed by Lee Mishkin.

Unlike the cels of the Tony Rivera’s three ghosts depicted in the book (p. 84), these were not suggested model cels of Belle but the same model from three different scenes, sequentially numbered, indicating they were random cels from those scenes. These were production cels!

I mention this in the audio commentary track on the new DVD release but here you have the opportunity to see the difference first hand. Tony's model of Belle, while simple, is still appealing but the animator for these scenes seems to have completely lost the charm inherent in the original design. As the DVD feature "From Pencil to Paint" shows, the animators relied heavily on the character layouts as guides for their animation, consequently the layout artist for this sequence also shares some responsibility. Rivera's clean graphic design has deteriorated into a series of undulating lines defining virtually nothing. A sensitive hand was needed to translate his graphic sensibility into animation; lacking that, a new approach was required.

Arguments could certainly be made regarding the quality of draftsmanship in the revised scene but this version of Belle is more feminine and far easier on the eyes. What was difficult to comprehend is that on a film which clearly did not have a luxurious budget, an entire sequence would make it all the way through the production process to final color, only to be redone. Making the decision to completely redo it was an expensive one although it also appears to have been the right one. To compare it to live action, it was as if the sequence had been shot with one actress only to realize there was no chemistry and it had to be recast and reshot with a new actress.

Labels:

Belle,

Lee Mishkin,

Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol,

Tony Rivera

Monday, November 15, 2010

Bob Singer, layout artist

In 1960, job opportunities abounded at UPA due to the studio’s sharp refocus from theatrical shorts to TV animation. The Mr. Magoo Show and The Dick Tracy Show , each with an order for 130 five minute shorts, necessitated a hiring binge. Corny Cole had called ex-roommate Bob Inman to come over and around the same time, layout artist Sam Weiss told his friend Bob Singer of an opening in the layout department. Singer, who was working at Warner Bros. as a background painter, was just beginning to cross over into layout and jumped at the chance to pursue it full time. He spent the next five years as a layout man at UPA.

Bob Singer started his career as a background painter for Shamus Culhane on the Bell Science films and also painted on the titles for Around the World in 80 Days. He was recommended for a storyboard job on the Bell films at Warner Bros. by Ben Washam, an animator in Chuck Jones’ unit, who had freelanced for Culhane. When those films finished, Bob began painting backgrounds for the McKimson unit, occasionally painting for the Jones unit and finally for Abe Levitow on A Witch’s Tangled Hare. He had just moved into layout and was about to join Freleng’s unit in that capacity when Sam Weiss made his fateful call to join him at UPA.

Between the conclusion of the TV shorts and the ramp up on Gay Purr-ee, Singer filled his time doing layouts for General Electric commercials featuring Mr. Magoo. On Gay Purr-ee, he was handed sizable sections of the film to stage and layout. Bob remembers:

When production began to wind down on the feature, Bob was picked to move on to Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol, the film that was moving through the studio right on the heels of Gay Purr-ee. Sequences Bob laid out were the titles, credits, the prologue with the song "Back on Broadway", Scrooge’s office, the graveyard and the epilogue after the play ends. Singer’s character and background layouts are highlighted throughout my book.

When production began to wind down on the feature, Bob was picked to move on to Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol, the film that was moving through the studio right on the heels of Gay Purr-ee. Sequences Bob laid out were the titles, credits, the prologue with the song "Back on Broadway", Scrooge’s office, the graveyard and the epilogue after the play ends. Singer’s character and background layouts are highlighted throughout my book.

The year 1963 was a slow one at UPA and appears to have been primarily filled with the production of GE commercials. When The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo was given the greenlight at the beginning of 1964, Singer was asked, along with Marty Murphy and Corny Cole, to help board the premiere episode, William Tell, and also laid out a chunk of the film. Bob worked on many of the episodes such as the four part Robin Hood, Paul Revere, Treasure Island and several others. Production had begun in January and although there were 26 episodes in the series, they were all completed and the entire artistic staff was laid off before the series made its debut in mid-September that same year. The last man out was Bob Singer, who fell back on his background painting skills to finish up a GE spot on his way out the door. Below is a page of Bob's storyboards from the William Tell episode and a layout from the Robin Hood episode.

From there, he briefly went to Tower 12, Chuck Jones’ operation which became the new incarnation of MGM, but left after a few short weeks due to what he felt was a creatively constrictive atmosphere. In October 1964, Bob began the longest stint of his career, at Hanna Barbera, eventually rising to the head of layout there. He worked on dozens of shows from Jonny Quest to Scooby Doo and everything in between. Of all the productions Singer worked on at HB, the one he was most proud of was art directing the feature, Charlotte’s Web. Bob finally decided to retire from the business in 1993.

Since then, he has kept active by writing and self-publishing a book on storyboarding and doing commissioned art featuring the Hanna Barbera characters. Although the book details the television production model for storyboarding, it’s recommended for its solid approach to production boarding, still applicable even with today’s technological methodology. If you would like to order a copy of the book or inquire about a personalized commissioned piece of art, you can contact Bob here.

In looking back on his career, Bob felt the artistic high point of his career was at UPA:

Abe (Levitow) was fortunate that he had assembled an excellent staff of artists who did good work in a timely fashion. Being an excellent artist himself, we all had a great deal of respect for him. With a boss like that you worked hard to please him and there was a good working environment in the studio, although filled with deadlines. I have worked in at least 16 different studios around town, as we all did, but I look at my time at UPA as the most pleasant and rewarding. Abe allowed his artists to have the freedom to invent, contribute and create without feeling the heavy hand of supervision and the ego that goes with it.

Bob Singer started his career as a background painter for Shamus Culhane on the Bell Science films and also painted on the titles for Around the World in 80 Days. He was recommended for a storyboard job on the Bell films at Warner Bros. by Ben Washam, an animator in Chuck Jones’ unit, who had freelanced for Culhane. When those films finished, Bob began painting backgrounds for the McKimson unit, occasionally painting for the Jones unit and finally for Abe Levitow on A Witch’s Tangled Hare. He had just moved into layout and was about to join Freleng’s unit in that capacity when Sam Weiss made his fateful call to join him at UPA.

Between the conclusion of the TV shorts and the ramp up on Gay Purr-ee, Singer filled his time doing layouts for General Electric commercials featuring Mr. Magoo. On Gay Purr-ee, he was handed sizable sections of the film to stage and layout. Bob remembers:

Since Chuck Jones wrote the story as a writer's storyboard, it was not suitable for production. We had to re-board most of it. I was assigned to do all the sequences occurring in the loft in Paris where our heroine was kept captive by the bad guy. Then I did all the layouts for that area, including following Musette as she escaped and ran through the streets. Another area I boarded and laid out began in a cafe where Jaune-Tom and his sidekick (Robespierre) were drinking and had a drunken spree that introduced a song sequence ending in a burst of fireworks. Also, near the end of the picture there was a sequence in Alaska, ending on a ship at sea which I again boarded and laid out.

When production began to wind down on the feature, Bob was picked to move on to Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol, the film that was moving through the studio right on the heels of Gay Purr-ee. Sequences Bob laid out were the titles, credits, the prologue with the song "Back on Broadway", Scrooge’s office, the graveyard and the epilogue after the play ends. Singer’s character and background layouts are highlighted throughout my book.

When production began to wind down on the feature, Bob was picked to move on to Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol, the film that was moving through the studio right on the heels of Gay Purr-ee. Sequences Bob laid out were the titles, credits, the prologue with the song "Back on Broadway", Scrooge’s office, the graveyard and the epilogue after the play ends. Singer’s character and background layouts are highlighted throughout my book.The year 1963 was a slow one at UPA and appears to have been primarily filled with the production of GE commercials. When The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo was given the greenlight at the beginning of 1964, Singer was asked, along with Marty Murphy and Corny Cole, to help board the premiere episode, William Tell, and also laid out a chunk of the film. Bob worked on many of the episodes such as the four part Robin Hood, Paul Revere, Treasure Island and several others. Production had begun in January and although there were 26 episodes in the series, they were all completed and the entire artistic staff was laid off before the series made its debut in mid-September that same year. The last man out was Bob Singer, who fell back on his background painting skills to finish up a GE spot on his way out the door. Below is a page of Bob's storyboards from the William Tell episode and a layout from the Robin Hood episode.

From there, he briefly went to Tower 12, Chuck Jones’ operation which became the new incarnation of MGM, but left after a few short weeks due to what he felt was a creatively constrictive atmosphere. In October 1964, Bob began the longest stint of his career, at Hanna Barbera, eventually rising to the head of layout there. He worked on dozens of shows from Jonny Quest to Scooby Doo and everything in between. Of all the productions Singer worked on at HB, the one he was most proud of was art directing the feature, Charlotte’s Web. Bob finally decided to retire from the business in 1993.

Since then, he has kept active by writing and self-publishing a book on storyboarding and doing commissioned art featuring the Hanna Barbera characters. Although the book details the television production model for storyboarding, it’s recommended for its solid approach to production boarding, still applicable even with today’s technological methodology. If you would like to order a copy of the book or inquire about a personalized commissioned piece of art, you can contact Bob here.

In looking back on his career, Bob felt the artistic high point of his career was at UPA:

Abe (Levitow) was fortunate that he had assembled an excellent staff of artists who did good work in a timely fashion. Being an excellent artist himself, we all had a great deal of respect for him. With a boss like that you worked hard to please him and there was a good working environment in the studio, although filled with deadlines. I have worked in at least 16 different studios around town, as we all did, but I look at my time at UPA as the most pleasant and rewarding. Abe allowed his artists to have the freedom to invent, contribute and create without feeling the heavy hand of supervision and the ego that goes with it.

Thursday, November 11, 2010

Joan Gardner, actress

She was a key performer in Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol and a staple of TV animation in the 60s and 70s yet today she is almost totally forgotten. Of all the cast members in Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol, perhaps the most difficult to find biographical information for was Joan Gardner. There was almost nothing on the internet, she had not been written about in any books and even newspaper articles were extremely difficult to find. To add to the confusion, there was also a British actress in Hollywood with the same name. However, with persistence, I finally was able to locate her cousin who was able to flesh out her story and provide me access to some of Joan’s personal memorabilia. Here, for the first time anywhere, is an overview of Joan Gardner’s life and career.

Joan, born in Chicago on November 16, 1926, came from a rich heritage of performers on both sides of her family. Her grandmother and mother, both named Adelaide, had a stage act, "Adelaide and Baby Cline" (Cline being her mother’s maiden name) and Joan began her show biz career appearing with them on stage at the age of five. Her father was famed jazz pianist, “Jumbo” Jack Gardner (so named because of his girth-at one point he was rumored to have weighed 400 pounds), who became one of the original members of Harry James’ big band. Her parents divorced when she was but a toddler, probably due to her father’s drinking habits (he was later fired by Harry James for drunkenness), and she and her mother moved to Los Angeles.

Soon thereafter, her mother married Edward Halpern, who, although he never adopted her, became the only father Joan ever knew. Joan Gardner continued her stage and musical training through her high school and college years and even had some bit parts in movies including a deleted scene in the 1947 Cecil B. DeMille film, Unconquered.

Her career in television began in January 1948 when she became an assistant production supervisor and writer for Stokey-Ebert TV Enterprises, the company that produced Armchair Detective (CBS, 1949) and Pantomime Quiz (1947-1959, CBS, NBC, Dumont and ABC). Both shows were filmed at KTLA, a local Los Angeles television station, which is how she ended up joining former Looney Tunes director, Bob Clampett, in December 1949 as a writer and performer for his television puppet show, Time for Beany, also filmed there. Joan provided the voice of Beany’s girlfriend, Susie, as well as the vocals for all the female characters.

(Below is behind-the-scenes look on the set of Time For Beany. You can see more images from this photo session at the Life Magazine photo library.)

Her mother, Adelaide Halpern, also contributed to Time for Beany, writing songs and special material including “Cecil the Sea Sick Sea Serpent” and “Beany” (i). Joan’s next gig with Clampett was in 1950 as head writer, puppeteer and assistant producer on another of his puppet series, Buffalo Billy, which originated out of CBS in New York; writers on the series were Bob Clampett, Don Messick and Gardner. (Adelaide Halpern also made musical contributions to this series). Many of the characters on Buffalo Billy later showed up on the 1962 animated series, Beany and Cecil, where Gardner once again found herself providing voices for Bob Clampett.

She took time off from her career when her stepfather passed away in 1952 but rejoined the work force in earnest a year later to help pay off the debts left from her stepfather’s sudden passing. Gardner re-signed with Clampett in 1953 to work on Flyboy, another daily puppet series out of the KTLA studios, where she supplied the voice of Flyboy himself as well as miscellaneous female characters. (The second photo below has Joan posing with legendary Hanna Barbera voice-over artist, Don Messick.)

Joan Gardner finally entered the animation field in 1958, voicing the character of the boy, Spunky, in Spunky and Tadpole for producer Ed Janis, whose Beverly Hills Productions produced the low budget animated show. The character of Tadpole was played at first by Don Messick, with whom she had worked on Flyboy, and later by Janis himself. The show lasted only three years although her association with Janis would continue for the rest of her life; they married in 1960.

Also in 1960, Gardner began her fortuitous relationship with UPA, doing voice work for The Mr. Magoo Show, the new TV cartoon series ushered in by Henry G. Saperstein. Next up was Gay Purr-ee for producer Lee Orgel, which led to her roles as Tiny Tim, the Ghost of Christmas Past, etc. in Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol. For 1964’s The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo, she contributed female voices for over 10 episodes, alternating between children, ingénues, matrons and villains for Sherlock Holmes, Noah’s Ark, Frankenstein, Don Quixote Parts 1 & 2, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Count of Monte Cristo, Snow White Parts 1 & 2, Rip Van Winkle and The Three Musketeers.

Gardner continued her writing career and made her big screen debut in 1965, penning the low budget beach party/horror film Surf Terror for producer husband, Ed Janis. The film saw release as The Beach Girls and the Monster, later running on TV as Monster from the Surf. (Newspaper articles during her lifetime would credit her with writing three different movies, using all three titles, although they were all one and the same.)

Between animation gigs on such other shows as The Flintstones, The Jetsons, Valley of the Dinosaurs and Snorks, Joan found work doing radio commercials and on camera roles in television commercials. As the 60s rolled into the 70s, Joan started working with Rankin-Bass on their TV specials, providing voices for The Mad, Mad, Mad Comedians, Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town, the second of her animated Christmas specials, and Here Comes Peter Cottontail.

Her last writing effort to make it to the big screen was the little known 1973 Western/horror film, A Man for Hanging, also produced by her husband. There was a later effort by Ed and Joan to film another one of her scripts, Scavenger’s Gold, but funding eluded them and it was never produced. (Right, Ed Janis and Joan Gardner, ca. 1973)

Joan Gardner died December 18, 1992, thirty years to the day from the debut of Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol. Sadly, Joan, her mother and grandmother all died fairly young from the same cause, cancer. Although her passion was writing, immortality seems to have eluded her there but she will always be remembered for her vocal performances in Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol and Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town, Christmas perennials viewed with fondness each holiday season by succeeding generations.

(i) There were announcements in the trades at the time that Halpern was to provide the theme song for a feature film version of Cecil the Sea Sick Sea Serpent, to be sung by Danny Kaye. The film was to be directed by former Looney Tunes director, Frank Tashlin.

Labels:

Adelaide Halpern,

Bob Clampett,

Don Messick,

Joan Gardner,

Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol,

Rankin Bass,

UPA

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)